Case Study essay paper

Case Study

9 – 3 1 7 – 0 1 9 A U G U S T 5 , 2 0 1 6

Professor Youngme Moon prepared this case. It was reviewed and approved before publication by a company designate. Funding for the development of this case was provided by Harvard Business School and not by the company. HBS cases are developed solely as the basis for class discussion. Cases are not intended to serve as endorsements, sources of primary data, or illustrations of effective or ineffective management.Case Study

Copyright © 2016 President and Fellows of Harvard College. To order copies or request permission to reproduce materials, call 1-800-545-7685, write Harvard Business School Publishing, Boston, MA 02163, or go to www.hbsp.harvard.edu. This publication may not be digitized, photocopied, or otherwise reproduced, posted, or transmitted, without the permission of Harvard Business School.

Y O U N G M E M O O N

S‘well: The Mass Market Decision

Late 2015, New York City. Sarah Kauss (HBS MBA 2003) took a sip from her 17-ounce teakwood S’well bottle as she studied the business proposal in front of her. Five years ago, Kauss had faced tremendous skepticism about whether consumers would spend $35 on what was essentially a high- end water canteen. She had since proven her skeptics wrong. In the five years since she had founded S’well, her metallic reusable bottle had become the preferred water accessory for eco-conscious fashionistas everywhere.Case Study

S’well now had partnerships with Fashion Week, Jimmy Kimmel Live!, and Universal Music Group, and was a coveted piece of swag in the technology industry, with prominent visibility at the TED Conference, SXSW, and companies like Facebook, Uber, Spotify, and Google. Sales in the past year (2015) had grown 500%, which meant Kauss would close the year with annual revenues of roughly $50 million.

But as founder and CEO, Kauss—who owned 100% of her company—was now facing one of her most difficult decisions to date. S’well had recently been approached by the giant discount retailer Target to produce a lower-priced bottle for 1,800 Target stores around the country. Over the past five years, Kauss had resisted offering her bottles to mass market retailers such as Target and Bed Bath & Beyond as she worked to build a premium brand at a premium price. Yet as Kauss pored over the proposal for the launch of a lower-priced bottle, she wondered, “Was it time to begin expanding the S’well product portfolio to the mass market?”

The Birth of S’well

As a student at Harvard Business School in 2001–2003, Kauss had no intention of becoming an entrepreneur. In fact, as a former Ernst & Young CPA, she wasn’t quite sure what she wanted to do post-graduation. “I knew I didn’t want to do consulting or banking,” Kauss recalled, “so I interviewed for everything.” She eventually ended up in commercial real estate development, leading the international business development division of a prominent US REIT (real estate investment trust), where she specialized inCase Study laboratories for top scientists around the world.

Even in those days, Kauss was passionate about water bottle waste: “Every day we would have these meetings, and at the end of every meeting, people would just throw their plastic bottles away. I would die.” Kauss’ zeal was motivated by a number of things: Americans used about 50 billion plastic water bottles each year, and manufacturing those bottles required more than 17 million barrels of oil

This document is authorized for use only by Michael Mata (mmata036@fiu.edu). Copying or posting is an infringement of copyright. Please contact customerservice@harvardbusiness.org or 800-988-0886 for additional copies.

317-019 S‘well: The Mass Market Decision

2

annually, enough to fuel 1.3 million cars. The bottles themselves took hundreds of years to bio-degrade, and if incinerated, generated toxic fumes. Recycling was only a partial solution—just one out of five bottles ended up getting recycled; the rest became litter. Moreoever, what many consumers didn’t realize was that most bottled water (including water sold under brands like Aquafina and Dasani) was simply purified tap water; there were very few brands whose water actually came from springs and mountain streams. All of these facts drove Kauss crazy.

For her part, Kauss always carried her own reusable canteen with her, a hot pink metallic bottle. The bottle wasn’t ideal in terms of functionality—cold water inside would warm up quickly, hot water wouldn’t stay hot, and the bottle itself would often sweat with condensation. Nor was the bottle very attractive—”I was a little embarrassed by how it looked because it didn’t really fit my aesthetic as a businesswoman.” Still, as Kauss put it, “I wanted to do my part to rid the world of plastic bottles.”

In 2010, Kauss found herself on vacation with her mother, who had recently survived a battle with breast cancer and was celebrating five years of being cancer-free. At one point during the vacation, her mother, who was in a particularly reflective mood, said, “You know, if I could go back in time and re- do my life, I would’ve spent my life painting.” She then turned to Kauss and asked, “What about you? What would you do with your life if you could do anything?” Kauss’s response was immediate. She told her mom: “I have this idea to create a sustainable metal water bottle that combines high function with beautiful fashion.” It was during this conversation that something clicked in Kauss’ mind, and by the end of the day, she was jotting down ideas for her business.Case Study

Not long after, Kauss quit her job and started S’well with her own money. In the five years since, Kauss had built S’well to reflect her personal vision for what a company should be—brand- differentiated, mission-driven, and operationally and financially disciplined. S’well bottles were made of the highest grade materials, with a unique look and shape. They were sold in the finest department stores and health clubs. The company had been profitable from day one. And S’well had established a reputation for giving back; it had a long-standing relationship with the U.S. Fund for Unicef in its efforts to bring safe drinking water to the world’s most vulnerable children. Kauss said:

I don’t know if it was the smartest thing or the dumbest thing to bootstrap this thing myself. It certainly made it tough to get the company off the ground. On the other hand, I think the reason S’well is so special is because I didn’t have anyone breathing down my neck in those early years, pressuring me to hit certain targets and metrics. I could say no to potential retail partnerships and customers that didn’t feel right. It was so important to me to build a premium brand. If I had had investors, they would’ve said, “How can you say no to Target? How can you say no to Bed Bath & Beyond?” Because the company belonged to me, I could do whatever I thought was best to build the brand.

The Brand Vision

Kauss’ vision for S’well began with the bottle itself. The 17-ounce double-lined, vacuum-sealed bottle was made of the highest grade 18/8 stainless steel. It was non-leaching, non-toxic, and did not sweat, while reliably keeping drinks cold for 24 hours and drinks hot for 12 hours. “I spent countless hours working to get every element exactly right—the insulation, the stainless steel, the design” Kauss said. “The bottle had to be extremely functional but also beautiful.” (See Exhibit 1 for a description of the bottle features.)Case Study

This document is authorized for use only by Michael Mata (mmata036@fiu.edu). Copying or posting is an infringement of copyright. Please contact customerservice@harvardbusiness.org or 800-988-0886 for additional copies.

S‘well: The Mass Market Decision 317-019

3

The bottles were priced eyebrow-raisingly high, with a minimum retail price of $35. “I wanted to be known as a luxury item,” Kauss explained. “To build a luxury brand with no budget, I had to do something to get people to pay attention to it. If the price was high enough, it would make people stop and say, ‘why is this bottle so different?’ And the reason is, it’s really two water bottles – one on the inside you don’t see, and one on the outside.”

A design firm helped Kauss come up with the name for her bottle, but to her dismay, she learned that the word “Swell” was not patentable because of its close association with the notion of water. Fortunately, an HBS classmate came up with a clever solution—to add an apostrophe to the word, and create legal protection around the logotype. “It was such a brilliant idea,” Kauss recalled. “People say, ‘where’s my S’well?, which is a great thing.”

Setting up the supply chain was a significant challenge. Kauss toured a number of facilities in China, but it took some time before she was able to identify a factory that met her standards for cleanliness, safety, and treatment of workers. “I wanted a supplier that did everything the right way,” Kauss explained. “I wanted the values of S’well to be reflected in every aspect of our business.”Case Study

The bottle originally came in just one color (Ocean Blue), but it didn’t take long before the company was producing bottles in a variety of colors and finishes. The company also made customized bottles with logos for companies and sports teams. (See Exhibits 2-3 for sample styles and custom designs). The stylishness of the bottle was essential to the company’s retail strategy; although other companies made stainless steel bottles, S’well bottles had to be gorgeous and sophisticated enough to penetrate high-end retailers.

Momentum Swells

In S’well’s first year of doing business (2011), the company was a makeshift operation. Inventory was piled everywhere in Kauss’s New York City apartment, and labels were printed out on her home computer. Kauss’ friends and parents were often enlisted to help fulfill orders. “There was one time when my dad accidentally stuffed my personal S’well bottle—filled with water!—into a box and sent it out to a customer,” Kauss laughed.

Kauss handled everything herself—customer service, selling, pitching to independent retailers. “I started by offering my bottle to independent fashion boutiques,” Kauss said. “I just walked into these stores and began pitching S’well. I then started to get into bigger retailers like Pure Yoga and Equinox. I was always focused on the best fashion stores, the best health clubs.” She traveled to dozens of trade shows (“I even built the trade show booths myself”), doing 17 shows in 2011 alone.

At one point, Kauss sent a bottle to Oprah magazine and was stunned to receive a reply. “The editor of the magazine took the bottle with her on her family vacation to Peru and came back saying, ‘I love this thing, it really works. I love the mission, I love everything and I want to put it in the magazine.’”

“This was a big moment for me,” Kauss said, “because right then I had to decide if I was going to invest more of my own money and really try to build a legitimate business. If I was going to be in Oprah magazine, I couldn’t be doing fulfillment myself, running my suitcase back and forth to the post office.” Kauss ordered tens of thousands more bottles and set up a warehouse.

As the company grew, Kauss started to nail some key retail accounts: Neiman Marcus, Equinox, Nordstrom, J.Crew, Athleta, and Apple’s Cupertino store. Kauss said, “All of these retailers were completely dubious about our price point. They just couldn’t believe a $35 water bottle would sell. So they would typically try us out by offering a few of our bottles on their online website, or they would

This document is authorized for use only by Michael Mata (mmata036@fiu.edu). Copying or posting is an infringement of copyright. Please contact customerservice@harvardbusiness.org or 800-988-0886 for additional copies.

317-019 S‘well: The Mass Market Decision

4

tuck some of our bottles away in a low-traffic section of their store. Of course, once they saw how quickly the bottles sold, they would move us into a much more high-profile location.” By the end of 2011, S’well was in 600 mostly independent retailers; consumers could also purchase the bottles via the S’well website.

Most of the company’s marketing efforts were devoted to building partnerships. For example, S’well provided thousands of bottles to the TED Conference and SXSW as well as to Mercedes Benz Fashion Week. Because the S’well bottle was so gorgeously photogenic, the company also received a significant amount of free marketing: Bloomingdale’s, Saks Fifth Avenue, and Nordstrom all featured S’well bottles in their mailers and catalogs, and the brand received positive PR coverage in numerous publications, including Vogue, InStyle, People, Shape, Women’s Health, and Buzzfeed.

Buzz about the brand was further bolstered by unsolicited plugs from high profile celebrities. Ellen DeGeneres, Jimmy Kimmel, and Tom Hanks were big fans, and The Big Bang Theory’s Kaley Cuoco regularly instagrammed her love for the product under the hashtag #obsessedwiththisbottle. (See Exhibit 4 for social media and public relations samples.) The actor Guy Pearce was such an avid customer that he insisted on featuring a beat-up version of a S’well bottle in his most recent movie, a post-apocalyptic film called “The Rover.”

All of this positive word-of-mouth translated into healthy growth. In its first year (2011), S’well sold $100,000 worth of bottles. In 2012, revenues doubled. In 2013, revenues jumped to $2 million. In 2014, S’well did $10 million in sales. And in 2015, the company was on track to do $50 million in sales, which amounted to roughly 3 million bottles. (See Exhibit 6 for sales channel breakdowns.)

Meanwhile, S’well continued its commitment to giving back. One of S’well’s most prominent partnerships included a contract with American Forests that stipulated that for every Wood Collection bottle the company sold, it would plant a tree. “If I had investors right now they’d probably toss me out on my ears because this one has been really costly,” Kauss noted. “We’ve planted half a million trees so far and next year we’ll plant thousands more.” (See Exhibit 5 for a sample of nonprofit partnerships.)

S’well in 2015

By 2015, S’well had come a long way. The company was now offering 30 different styles in three different sizes (9, 17, and 25 ounce). Retail price points remained high—the minimum retail price for the 9-ounce version was $25, the 17-ounce version was $35, and the 25-ounce version was $45. By now, the product portfolio was constantly rotating: “We follow the same calendar as fashion brands,” Kauss noted. “We release two seasonal lines a year, so we are always introducing new designs and phasing out old ones.”

The company offered designer exclusives as well. For example, S’well had just signed a partnership with designer Mara Hoffman, who had recently begun offering a high-end line of ($400) yoga pants. These limited-time exclusives were sold at a premium price and offered only to certain key accounts. The company rarely had to chase these kinds of partnerships; Kauss regularly fielded requests from companies ranging from Swarovski (who wanted S’well to do a super-premium crystal bottle) to Mattel (who wanted S’well to do a Barbie collaboration) to engage in design collaborations.

Although Kauss managed the product portfolio and drove all of the key strategic decisions herself, the company had grown to include 35 employees working in sales, marketing, ecommerce, customer service, and operations. As one S’well staffer put it, “It’s an exciting place to work because people just

This document is authorized for use only by Michael Mata (mmata036@fiu.edu). Copying or posting is an infringement of copyright. Please contact customerservice@harvardbusiness.org or 800-988-0886 for additional copies.

S‘well: The Mass Market Decision 317-019

5

love our product so much. Sometimes they’re a little confused at first and the price point definitely creates doubt, but once they try it, they fall in love. There’s never been a case where we place our bottles in a store and it doesn’t sell through. The brand just moves.”

S’well + Starbucks

One of the most significant partnerships S’well had been able to establish was with Starbucks. The origins of the partnership could be traced back to 2012, when S’well was just a three-person team (Kauss and her first two employees) operating out of a tiny WeWork office in New York City. Kauss was sitting at her computer one day when she received an email from Starbucks saying the company had been following S’well’s progress and would love to meet.

“I remember sitting there, staring at my computer screen in this tiny office, thinking, what do I do now?” Kauss remembered. “Remember, back then I was just getting started, and although I had this ambitious strategic vision for S’well, I wasn’t ready to reveal anything yet. So I was nervous. Do I go to Starbucks and share everything, or do I not reply and risk having them work with another company?”

Kauss ended up flying to Seattle, where she met with Starbucks’ merchandising group and told the whole story of her brand. “They loved it,” she said. “It was a little emotional for me.” But while Starbucks clearly wanted to work with her, the Starbucks merchandising team was skeptical that consumers would be willing to pay such a high price for a brand they had never heard of. Kauss recalled:

This was one of the most difficult conversations I’ve ever had in my professional career. I decided to hold my ground. I said to Starbucks, if you want to work with us, here are our terms: (1) you have to agree to our minimum advertised price; (2) you have to agree to our wholesale price; and (3) you have to agree to display the S’well brand prominently. The reason I felt so strongly about these three terms was I didn’t want to become a Starbucks bottle. I was trying to build a brand. Fortunately, Starbucks ended up agreeing to our terms and to this day they have been a great partner.

Because Starbucks was manifestly committed to socially responsible business practices, it only worked with companies with supply chains that were above reproach. This is where Kauss’ earlier pickiness in selecting a supplier paid off: “Starbucks does a ton of factory certification and it’s been a real competitive advantage for us. Even if another brand wanted to try to compete with us for Starbucks’ business, it would be hard for them to get a factory with sufficiently high quality standards up and running very quickly.”

Starbucks’ first test with S’well took place in 2013, when the coffee retailer put S’well bottles in 140 Starbucks locations in Austin and Atlanta. Because the test was somewhat rushed, there was no time to create proper signage or merchandising displays for this trial run; Starbucks simply purchased a bunch of S’well bottles and stuck them on the shelves. Nonetheless, S’well almost immediately became one of Starbucks’ fastest-selling items of all time. Starbucks then expanded the trial to specific locations in New York City’s Times Square, Hawaii, Las Vegas, and University of Washington.

By 2015, Starbucks made the decision to embrace the S’well partnership wholeheartedly, by committing to put S’well in 14,000 locations in the U.S., as well as in its coffee outlets in 15 countries in Asia and 37 countries in Europe. The massive rollout was still underway—by December of 2015, S’well was just beginning to appear in domestic and Asian locations, and was on track to be Starbucks’ shelves

This document is authorized for use only by Michael Mata (mmata036@fiu.edu). Copying or posting is an infringement of copyright. Please contact customerservice@harvardbusiness.org or 800-988-0886 for additional copies.

317-019 S‘well: The Mass Market Decision

6

in Europe by the summer of 2016. (See Exhibit 7 for sample Starbucks bottle.) In addition, the company was in early discussions to expand the partnership further with additional products. Kauss reflected:

Some people may criticize the Starbucks deal because it makes S’well too much of a mass brand. I thought about this a lot, and ultimately I decided it was a great partnership for us. Starbucks is one of the world’s most respected, socially responsible companies. And if the mission of S’well is to get as many people as possible to use a reusable bottle, the Starbucks partnership gives us great access. Is our presence in Starbucks going to make it harder to remain elevated as a luxury brand? I don’t know. Maybe it’ll help keep us elevated, I don’t know. But I think it’s a risk worth taking.

The Competitive Space

S’well was not the only brand competing in the reusable water bottle space. Competitors included BPA-free plastic water bottle brands such as Nalgene and CamelBak, as well as stainless steel brands such as Sigg, Klean Kanteen, and Thermos. (See Exhibit 8.) Most of these competitive products had lower price points (as low as $5 to $10) and were sold in sporting goods stores and mass retailers. They differed significantly from S’well in terms of physical appearance and branding.

Of greater concern to Kauss were the many copycat bottles entering the market. These products blatantly imitated S’well’s shape, features, and overall appearance, and what Kauss was discovering was that legal protections were not enough to dissuade these copycatters from producing their knock- offs. (The S’well logo, wordmark, and bottle shape were all trademarked, although the legal protection of the bottle shape was not quite as strong as that for the logo and wordmark.)

The most conspicuous place to find these copycat products was on Amazon. A simple search for the term “Swell bottle” turned up copycat items from no-name manufacturers and distributors like Aomerly, Flexware, Aquaflask, and others. (See Exhibit 9 for examples.) Most of these bottles had a similar appearance to S’well bottles, but were manufactured at lower quality standards and were offered at a retail price ranging from $15 to $25 for a 17-ounce bottle.

S’well’s initial response was to send cease & desist letters to these sellers, but most of its letters went unanswered. S’well then tried appealing directly to Amazon, but to no avail. The situation was frustrating for Kauss; there seemed to be no clear answer as to how her company could protect itself against these knock-offs. Kauss mused:

At the end of the day, our customers are going to be people who really care about buying a meaningful brand with legitimate values and authentic positioning. The copycats sold on Amazon are offered by low-margin sellers who aren’t trying to build a brand, they’re just trying to make a quick dollar drafting off of our success. For now, we’ve decided we’re comfortable allowing this fragmented, unbranded copycat market fight for the low-end of the market. Meanwhile, we’re going to stay true to our own strategy of driving brand awareness at the higher end of the market.

Interestingly, although S’well had made a conscious decision not to sell its products through Amazon, certain Amazon resellers did offer authentic S’well bottles via the Amazon website. These resellers would purchase the bottles directly from S’well’s website, and then resell them via Amazon for an even higher retail price than S’well’s retail price. Although this practice appeared to be in violation of Amazon policy, S’well had not taken action against these resellers. “This kind of activity doesn’t bother me as much,” Kauss explained. “These resellers are selling our authentic bottles, and

This document is authorized for use only by Michael Mata (mmata036@fiu.edu). Copying or posting is an infringement of copyright. Please contact customerservice@harvardbusiness.org or 800-988-0886 for additional copies.

S‘well: The Mass Market Decision 317-019

7

they’re doing it a price that is even premium to our own. It doesn’t appear to be hurting our brand; in fact, in some ways, it’s an indication of how much people are willing to pay for an authentic S’well bottle.”

Finally, S’well had to contend with lower-priced competitive products that, while not overt knock- offs, were similar enough to cause potential consumer confusion. Oggi was perhaps the most prominent of these competitors. The stainless steel Oggi bottles were double-walled and insulated, but with a slightly different shape than S’well bottles. They cost about $15 for a 17-ounce version, and were sold in discount retailers like Sam’s Club, TJ Maxx, and Marshalls, places where S’well bottles were not sold. The company behind Oggi had done little to build the Oggi brand (there wasn’t even an Oggi website), and the bottles tended to garner tepid reviews from online websites (the 3 out of 5 star rating on the Bed Bath & Beyond website was typical), but there was no question the bottles were generating real sales at the low end of the market.

The S’ip Decision

Back in her lofty New York City S’well headquarters, Kauss considered the decision in front of her. Much of her efforts over the past five years had been toward proving it was possible to build a premium brand in the reusable water bottle category. Now she was facing real competitive pressure from the mass end of the market. She said, “I know we’ve always said no to mass retailers like Target before, but we’re in a different place than we were five years ago, and it may be time for us to reconsider.”

Over the past few months, Kauss and her team had spent a significant amount of time exploring in depth the idea of a lower-priced bottle. Indeed, Kauss believed that in order to fully determine the merits of the idea, it was important to flesh out the proposal in some detail.

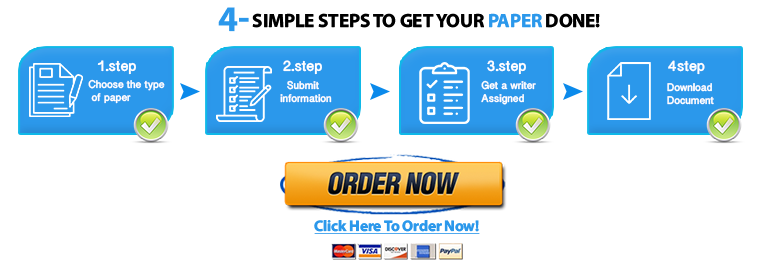

As it stood, the proposal looked like this:

S’well would expand its product line to include a new, lower priced bottle that would retail under the sub-brand of S’ip. The brand signage would be marked as: “S’ip by S’well.”

The S’ip bottle shape would be visibly different from that of the S’well bottle.

The S’ip bottle would be available in one size only (15 ounce).

The S’ip bottle would retail for $25.

For the first six months, the S’ip bottle would be sold exclusively through Target. After that, distribution would potentially expand to include other mass market retailers. “The reason we are thinking of starting with Target is they have a history of doing all kinds of cool brand collaborations, like the Lily Pulitzer partnership they did this past year,” Kauss noted. “In addition, they just love the S’ip concept we’ve shown them. They have promised to put it in all 1,800 of their stores, with prominent end cap display for the first six months.”

The style philosophy for S’ip would be different from that of S’well—more playful, more youthful, more whimsical, with tiny patterns of things like squirrels, bicycles, bacon and eggs— targeted toward children and teenagers, as well as mothers shopping for their families. (See Exhibits 10 for concept photos.)

This document is authorized for use only by Michael Mata (mmata036@fiu.edu). Copying or posting is an infringement of copyright. Please contact customerservice@harvardbusiness.org or 800-988-0886 for additional copies.

317-019 S‘well: The Mass Market Decision

8

The risks were obvious. The decision to move forward would require a significant operational investment—at the very least, a new factory would need to be brought on line and scaled quickly to meet production demand. In addition, the overall challenge of managing supply-and-demand would become much more complicated. “If Starbucks sells out of our bottles, they don’t need us replenish immediately; they are okay with empty shelves,” noted Kauss. “At Target, if you have an empty shelf, you lose the space unless you can replenish immediately. It’s a whole different ballgame to deal with mass retailers. It means we would need to get much more sophisticated in how we analyze sell-through data and figure out which styles are working and which aren’t. Currently with S’well, not every style has to move in order for it to contribute to our brand portfolio.”

As Kauss considered the S’ip decision, a number of additional considerations weighed on her. The company clearly lacked the bandwidth to effectively launch and manage the S’ip extension; the S’well team, which consisted of about 35 employees, was consumed with managing the growth of the S’well brand. The Starbucks partnership alone was projected to accelerate the business in a dramatic way in 2016, and Starbucks was already talking about expanding the partnership even further. In fact, although discussions with Starbucks were just beginning, some of the concepts flying around were exciting and potentially game-changing.

As for Kauss herself, she, too, was stretched thin. She was currently operating as both CEO and CFO. She also operated as head of product development, while managing the overall product portfolio and personally handling key relationships like Starbucks. If the company were to move forward with the S’ip launch, Kauss would need to grow her team quickly. Could the company scale rapidly enough to manage the requirements of a mass market product launch? If it were to try to do so, Kauss was, for the first time in the company’s history, considering taking outside money to help capitalize the business. This would represent another significant step in the evolution of the company.

Of course, the opportunities were obvious and significant as well. A lower-priced S’ip line would open up a myriad of new channel possibilities, including big box retailers, mass market sporting goods stores, and low-priced department stores. “It would allow us to begin steering all mass market demand to our S’ip product line, while continuing to steer our high end demand to S’well,” Kauss said. “Of course, cannibalization is always a concern. On the other hand, if anyone is going to cannibalize us, maybe it should be our own brand.”

Kauss studied the S’ip proposal in front of her. Was now the right time to launch S’ip?

This document is authorized for use only by Michael Mata (mmata036@fiu.edu). Copying or posting is an infringement of copyright. Please contact customerservice@harvardbusiness.org or 800-988-0886 for additional copies.

S‘well: The Mass Market Decision 317-019

9

Exhibit 1 The S’well Bottle

Source: Company documents.

This document is authorized for use only by Michael Mata (mmata036@fiu.edu). Copying or posting is an infringement of copyright. Please contact customerservice@harvardbusiness.org or 800-988-0886 for additional copies.

317-019 S‘well: The Mass Market Decision

10

Exhibit 2 S’well Sample Styles

Source: Company documents.

This document is authorized for use only by Michael Mata (mmata036@fiu.edu). Copying or posting is an infringement of copyright. Please contact customerservice@harvardbusiness.org or 800-988-0886 for additional copies.

S‘well: The Mass Market Decision 317-019

11

Exhibit 3 S’well Sample Custom Products

Source: Company documents.

This document is authorized for use only by Michael Mata (mmata036@fiu.edu). Copying or posting is an infringement of copyright. Please contact customerservice@harvardbusiness.org or 800-988-0886 for additional copies.

317-019 S‘well: The Mass Market Decision

12

Exhibit 4 Social Media and PR Buzz

Source: Company documents.

KELLY RIPA

OLIVIA WILDE

KALEY CUOCO

ROSARIO DAWSON

KATHERINE POWER

BETTY WHO

NIGEL BARKER

@TOASTMEETSWORLD

GUY PEARCE

This document is authorized for use only by Michael Mata (mmata036@fiu.edu). Copying or posting is an infringement of copyright. Please contact customerservice@harvardbusiness.org or 800-988-0886 for additional copies.

S‘well: The Mass Market Decision 317-019

13

Exhibit 5 S’well Nonprofit Partners

Source: Company documents.

This document is authorized for use only by Michael Mata (mmata036@fiu.edu). Copying or posting is an infringement of copyright. Please contact customerservice@harvardbusiness.org or 800-988-0886 for additional copies.

317-019 S‘well: The Mass Market Decision

14

Exhibit 6 S’well Sales Channels as of 2015 (percentages approximate)

Percentage of Total Sales Description

E-Commerce 25% Direct-to-consumer sales from S’well’s own website. Bottles sold

for $25, $35, and $45 plus $8 flat rate shipping (free above $100).

Boutique 20% Wholesale sales to over 2,000 small, independent domestic

specialty retailers. Bottles sold for $12.50, $16, and $22. Average

order size of $500. Sales driven through trade shows, direct

outreach and wholesale portal.

Custom 10% Sales of special order, custom-branded bottles to partners such as

BMW, TED Conference, The Nature Conservancy, Equinox, Apple,

etc. Bottles sold for $20 to $35 with logos or multi-color etchings.

Sales driven by a dedicated custom sales professional.

Key Accounts 10% Sales to large retail partners such as Williams Sonoma, Saks Fifth

Avenue, Neiman Marcus, Bloomingdale’s, Athleta, The Container

Store, Nordstrom, etc. Relationships acquired through direct sales

efforts and trade show exposure. Does not include Starbucks.

International 20% Sales to international distributors. Orders range from $10k to

$1mm.

Source: Company documents.

This document is authorized for use only by Michael Mata (mmata036@fiu.edu). Copying or posting is an infringement of copyright. Please contact customerservice@harvardbusiness.org or 800-988-0886 for additional copies.

S‘well: The Mass Market Decision 317-019

15

Exhibit 7 Sample Starbucks Bottle

Source: Company documents.

This document is authorized for use only by Michael Mata (mmata036@fiu.edu). Copying or posting is an infringement of copyright. Please contact customerservice@harvardbusiness.org or 800-988-0886 for additional copies.

317-019 S‘well: The Mass Market Decision

16

Exhibit 8 Competitive Bottle Brands

Source: Company documents.

This document is authorized for use only by Michael Mata (mmata036@fiu.edu). Copying or posting is an infringement of copyright. Please contact customerservice@harvardbusiness.org or 800-988-0886 for additional copies.

S‘well: The Mass Market Decision 317-019

17

Exhibit 9 Sample Screenshot of Amazon Website Search for “S’well Bottles”

Source: www.amazon.com, accessed March 2016.

This document is authorized for use only by Michael Mata (mmata036@fiu.edu). Copying or posting is an infringement of copyright. Please contact customerservice@harvardbusiness.org or 800-988-0886 for additional copies.

317-019 S‘well: The Mass Market Decision

18

Exhibit 10 S’ip Concept Photos

Source: Company documents.

This document is authorized for use only by Michael Mata (mmata036@fiu.edu). Copying or posting is an infringement of copyright. Please contact customerservice@harvardbusiness.org or 800-988-0886 for additional copies.